The Best and Worst of Times for the Japanese Anime Industry - Belated Post-Mortem

For every success, there's much in drama and sensationalism.

At the time the original piece was written for Areo back in 2022, Japan’s anime industry stood at a peculiar crossroads: at one experiencing one the best periods in its history, yet also beset with issues that fueled much pessimism in certain corners of fandom. While much of that remaining the same in 2024 isn’t much of a surprise, what has drawn more attention is how much that pessimism and outright fearmongering is being fueled by narratives that have become nigh-well entrenched over the years. So much so that in a way, it’s a meme that refuses to die. Then again, for every success, there’s much in drama and sensationalism, as well as those trying to take advantage of the latter for their own gain.

The Best and Worst of Times for the Japanese Anime Industry

Disclaimer: This article was originally posted on Areo Magazine on February 21, 2022. This has been republished in light of the publication shutting down business operations on November 6, 2023. Few who follow developments in the world of anime doubt that Japan’s animation industry is a global juggernaut—an enduring, profitable symbol of soft power—as po…

This partially stems from how such rhetoric does have a grounding in current events. MAPPA, which had already been gaining notoriety for its working conditions, was at the center of renewed controversy following a string of social media meltdowns from staff and animators involved with the second season of Jujitsu Kaisen over the later half of 2023, citing mistreatment, poor compensation and tight deadlines. The Animator Dormitory Project, meanwhile compiled many such comments and testimonies into a scathing feature on February 10, 2024 which further indicted the studio and others like it. Though this was inevitably covered internationally by Screen Rant two weeks later as reflecting a grim future, said article also highlighted how it’s not doom-and-gloom, whether it’s government-backed initiatives to train new blood to make up for shortfalls or studios like Kyoto Animation, Studio Pierrot and Studio BONES to curb bad practices. Such details, however, aren’t given as much attention, being buried much further down while the bleakness is amplified.

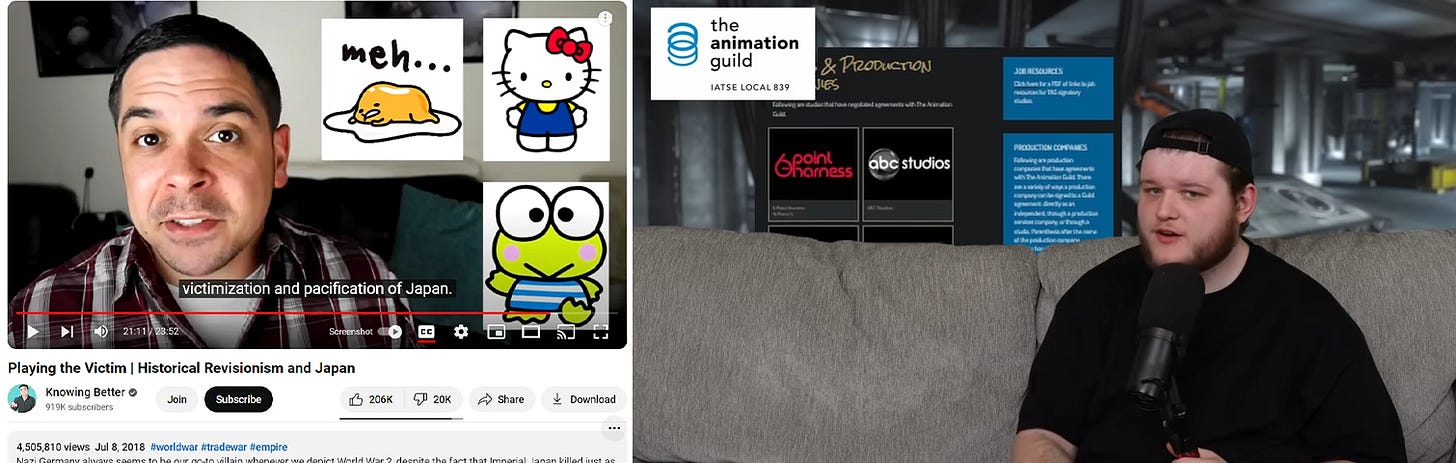

It also stems from how coverage on the anime industry in platforms like YouTube has been nigh-consistent in propagating such narratives, which became harder to ignore while compiling research for a recently-published dive into misleading and agitprop video essays. Youtuber Knowing Better’s “Playing the Victim” from July 18, 2018 notably helped re-popularize the notion that Japan was using otakudom and the very idea of kawaisa (“cuteness”) as a ploy to whitewash the memory of the Second World War, foreshadowing the sleight-of-hand later used by Moon Channel when pushing his conspiratorial claims on anime. Meanwhile, Lextorias’ recent “Why Is Adult Animation So Far Behind?” from July 27, 2024 invokes many of the same points HitReg made about how “anime is dying” in describing the Japanese scene compared to the American one towards the last third of the video. Yet while acknowledging the efforts of KyoAni as well as the Animator Dormitory Project, they’re still downplayed in favor of pushing unionization in the style of Hollywood’s unions as a silver bullet answer.

Disregarding how the seeming rise of Chinese animation is being scapegoated by some figures like MAPPA chairman Masuo Maruyama in an attempt to position themselves as the solution (even while China’s creatives face increasingly repressive censorship lest they face reprisals from the ruling Communist Party), it’s little wonder such narratives are all but taken for granted. Figuring out how and why this is sustained, however, requires digging deeper past the headlines and into how this is all presented to begin with, not just by “tourists” unfamiliar with the anime industry but also those who claim to be experts on it. Something that’s exasperated by there being sources from within the industry itself fueling this rhetoric, whose voices are given much more pronounced attention at the expense of others.

A consistent thread in the overall discourse has been to not simply invoke the “Curse of Osamu” (which Roland Kelts described as pushing shows to networks at prohibitively low cost), but pin the blame squarely on Osamu Tezuka and his Mushi Production for ruining anime. Such sentiment has notably been vocally endorsed by Hayao Miyazaki who, shortly after Tezuka’s death in 1989, scathily condemned him for doing nothing good for the industry. It’s likewise little coincidence that the Studio Ghibli auteur and his close associates (who themselves were involved in pushing for Toei’s unionization) are constantly referenced as though they had the final say, capitalizing on their influence. These put together have helped reshape how the topic is being approached at all, with Miyazaki’s oft-memed “anime was a mistake” invoked to throw shade on otaku. This has also leaked into how anime history is framed in social media, such as some acting as though the mecha genre didn’t come of age until Neon Genesis Evangelion’s deconstructive commentary on otakudom.

Putting aside Miyazaki’s infamously dour and divisive views being a consistent aspect going back to the 1980s, it does not take much to see “evidence” corroborating them. FLCL creator Toshimuchi Otsuki and Ergo Proxy writer Dai Sato infamously blamed the popularity of moe and slice of life shows for killing the industry over the 2000s. Hideaki Anno was notably quoted at the 2014 Tokyo International Film Festival saying how anime’s days were numbered unless they could be made “without commercial considerations.” The reality, however, is anything but one-sided. For all of Tezuka’s flaws, he notably treated and paid his employees well, as attested to in a 2020 interview with Mushi Pro alumnus and Gundam co-creator Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, with the fault instead traced to the global economic downturns of the 1970s. Coincidentally, many who worked under Tezuka also went on to build upon what worked to help improve the state of the industry down the line, such as those who went on to build Sunrise and KyoAni.

Even the much-invoked answer of unionization, considered by video essayists like Lextorias as a key advantage the Anglophone West has over anime (such as purportedly better pay, representation and working conditions), may not be be-all-end-all answer it’s being sold as. Across the Pacific, there’s been growing awareness that outsourcing, expensive production costs, growing layoffs, and AI are threatening American animation, as highlighted in a May 11, 2024 piece by industry veteran Zach Mulligan. Increasingly, however, there’s also been growing pushback among more than a few animators against the status quo enabled by the very Hollywood unions leading the strikes, and unlike decades ago, they have much less power to counter those problems. One gets the impression that replicating the California experience in Japan would not only repeat many of the same issues, but also risks creating a self-fulfilling prophecy, on top of neglecting what some Japanese studios are doing independently of such silver-bullet solutions.

The colorful tapestry that’s the anime industry, warts and all, is undoubtedly one that’s worth delving into. Yet it is one not only buried under sensationalized doom-and-gloom, but also obscured by those claiming to either represent the discerning critic or save Japan from itself. Pushing back against such pessimism and outright misinformation could lead to being accused of peddling “conservative” anti-union propaganda, belittling legitimate concerns, or simply holding creators back. As much as going against the grain can seem like a tall order, perhaps it’s all the more necessary in order for not only anime to move forward, but animation as a whole. It may not be sensational and eye-grabbing, but it’s preferable to allowing tired memes or questionable narratives to persist into the next generation.