The Future of Western Comics?

A retrospective on ComicsGate, its complicated legacy, and the modern American comics industry.

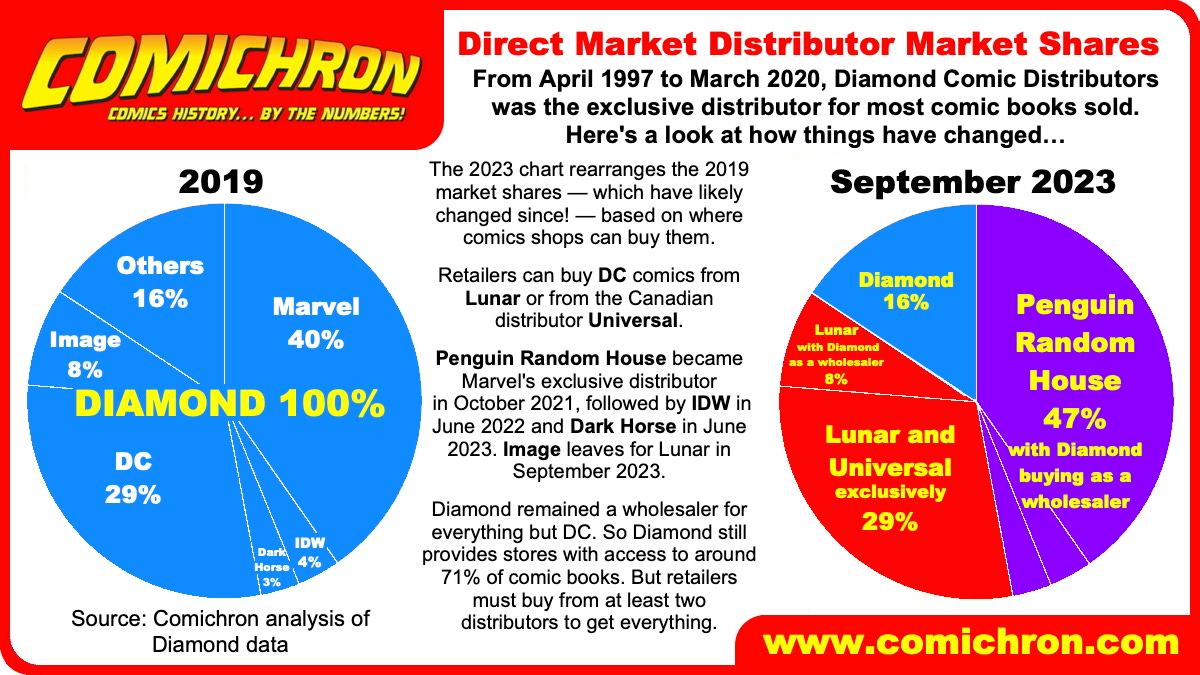

When it comes to the world of Western comics, an outsider may get the impression of an unstoppable mainstream behemoth that leaves little room for anyone else trying leave their mark. The cultural dominance of the Marvel Cinematic Universe alone in the popular consciousness, at least up until recently, seems to make this self-evident. Look past the multimedia adaptations, however, and a different picture starts emerging. According to online database Comichron, the North American market saw overall direct market sales being around $43-45 million as of April 2022 (the last known point in which such data was publicly available). While this superficially reflects a dramatic rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic and a 14-19% increase from the same period in 2019, there are myriad issues (ranging from stifled creativity to hyper-partisanship and diminishing returns in profits) that threaten to undermine the status quo in the long run.

I’ve touched on much of these issues, as well as how Japanese manga are surpassing American comics, in both a 2021 piece for Areo Magazine and a follow-up post-mortem earlier this month. These are thanks in no small part due to greater diversity of content, better economics, general professionalism among creators, and a healthier respect towards audiences. Even putting aside the competition overtaking the industry in North America to the point of becoming common knowledge, according to CBR on December 9, 2023, it’s evident that this can’t be sustained indefinitely. This is where ComicsGate comes into the picture.

Among all the various efforts among comic fans and creators seeking to change course from a self-destructive path, this is perhaps the most notorious. As detailed on a now-deleted wiki page, it’s presented as a hashtag and consumer revolt against “the awkward, stilted injection of [Progressive] political messages into stories regardless of whether context demands for it or not”. Beyond that, in its supporters’ eyes, it became a rallying cry for supporting, and creating, an alternative scene that would serve as an example for others to follow.

Others, however, came to view this as an “Alt-Right” harassment campaign holding back change, bogged down by infighting and its cheerleaders’ hubris. Tempting as it may be to dismiss this as ineffectual online drama, its legacy is much more complicated that it’s often seen. For better or worse, this reflects a legitimate shift in the future of Anglophone comics. Albeit, it’s one that the industry‘s mainstream neglects to its own peril.

The Origins and Rise of ComicsGate

According to commentator A.J. Glickson, the earliest known mention of ComicsGate as a hashtag dates back to a 2014 tweet by Israeli blogger Avi Green, used as wordplay to describe Marvel’s attempts to rewrite its own history. Getting a clear understanding of the movement beyond social media, however, requires seeing what Anglophone comics were becoming by then.

Even as the self-censoring and repressive Comics Code Authority (established in response to moral panic against comic books in 1954 over their perceived harmful impact on the youth) petered out into irrelevance, with Archie Comics being the last to fully abandon the seal by the end of January 2011, publishers and creators alike sought to pursue more serious, topical subjects. This had been decades in the making, with the late Stan Lee notably among the first to openly taunt the censors by publishing a Spiderman story about drug abuse in 1971, which was considered taboo simply for bringing the subject up.

From “indies” to mainstream issues published by the “Big Two” of Marvel and DC Comics, this trend seems admirable on paper. Yet in practice, this more often than not meant making politics (particularly along “woke” or American progressive lines) and the authors’ personal agenda a focal point of the stories themselves, to the detriment of their overall quality. Whether out of a misguided attempt at making ennui-inducing "arc fatigue" seem fresh, pandering to activists for new audiences, or deliberately antagonizing existing ones for extra sales, such grandstanding alienated long-time fans even as the market continued shrinking.

On October 2016, Marvel cancelled the comic run of Mockingbird, a series about a female operative which notably touted feminist political rhetoric as a selling point. Despite a streak of critical praise from mainstream industry outlets like CBR and IGN, this translated into poor sales which couldn’t sustain a full run. Writer Chelsea Cain, however, not only ascribed the subsequent criticism and mockery as misogyny, but soon lambasted a sizable portion of comic fans as being “dominated by sexist jerks.”

Allegations of harassment garnered her support from her former employer and publications like Buzzfeed, although no clear evidence proving such claims ever surfaced, according to journalist Brad Glasgow. It didn’t stop Bleeding Cool’s Joe Glass on August 6, 2017, who used this, as well as criticism over Marvel assistant editor Heather Antos tweeting a picture of herself and her fellow co-workers getting milkshakes, (symbolically flaunting the company’s ostensibly progressive pretensions) to double-down on branding fandom at large as reactionary trolls. With how he also used the article to justify restricting freedom of speech in the name of protecting minorities, it’s as though the CCA had resurfaced with even less qualms or oversight.

It wasn’t until a month later that this brewing tension truly boiled over. Indie publisher IDW had assigned writer Aubrey Stitterson with handling its G.I. Joe adaptations, despite having no prior experience with (and in hindsight a rather dismissive approach to) the classic ‘80s franchise. Under his watch, well-established characters were either needlessly race-lifted or distorted into politicized caricatures that couldn’t make for disjointed plots and bad art. So when Stitterson not only used his social media presence to make a sneering, unprofessional remark about the 9/11 attacks, but subsequently insulted series critics and relatives of victims alike, it was effectively the final straw.

Neither IDW’s attempts at damage control (including its cancellation of a planned spinoff penned by Stitterson due to poor sales), nor Bleeding Cool’s attempts to frame critics as “anti-diversity trolls” could stem the backlash. If ComicsGate hadn’t already begun, it may as well have.

The Rise of ComicsGate

Initially, this was little more than amorphous social media outrage and criticism, echoing the early phases of GamerGate, as I touched on back in December 2023. It would not stay that way for long, however.

Three people stood out from the onset to take the initiative: commentator Richard C. Meyer (known then by the moniker Diversity & Comics on YouTube), former DC illustrator Ethan Van Sciver of Green Lantern fame, and freelance artist Jon Malin (who’d been involved with several Marvel titles). They found common ground over how the status quo had become increasingly toxic and censorious against anything the deviated from it. Based from their own experiences working with the Big Two, they also came to the conclusion that trying to implement reforms from within was a fool’s errand, when having the “wrong” political views could derail one’s career, or worse. Tapping into the brewing discontent, they soon attempted to give some semblance of structure, and a longer-term plan. To that end, Meyer announced that he would write a new intellectual property called Jawbreakers (about ex-superheroes turned mercenaries), while Van Sciver revived his old indie character Cyberfrog as a crowdfunded project.

Other creators joined in as the hashtag become a movement. These included Earthworm Jim creator Doug TenNapel and DC artist Chuck Dixon (known for his work on Batman in the ‘90s), as well as sympathetic industry veterans like Blake Northcott (who made her name writing for various publishers such as Aspen Comics). There were also myriad lesser-known figures, such as freelancer Timothy Lim, whose portfolio ranges from licensed merchandise artwork to political parodies like Wall-Might (a comedic take on the Trump presidency inspired by the manga My Hero Academia), and an upstart team comprised of Trent Luther, Brian Ball, and Luigi Tuerel, whose first work would become RAGS Zombie (the adventures of military vets disguised as a zombie apocalypse tale). While many tended to have conservative, center-right or classical liberal views, there was a marked diversity of opinion, which translated into a wider variety of subject matter than what’s offered by mainstream platforms, ranging from gritty period pieces to affectionate homages to classic superheroes. Even if it made for at-times disjointed agendas, many seemed nonetheless united by a desire for proactive change, for freedom to make what they liked to do irrespective of politics, and giving fans what they wanted.

By August 2018, as highlighted by Bounding into Comics’ John Trent, it seemed like ComicsGate’s aspirations were starting to pay off. Many works done by either creators aligned with it or those seen by supporters as alternatives, were noted as having had tens, if not hundreds of thousands in dollars raised for their respective projects (with Meyer’s Jawbreakers for instance raking in over $374,000). Even other smaller indie publishers such as Dynamite Entertainment (known adapting classic 20th century pulp heroes like Flash Gordon and The Shadow for modern audiences) were openly lending their support for the hashtag. It looked as though fans were voting with their wallets to a degree that hadn’t been seen outside the Big Two or elsewhere in the American comics industry in recent years.

Even at the cusp of apparent success, however, crises weren’t far behind.

Backlash and Apparent Downfall

2018 saw multiple pieces from both industry sources and mainstream outlets like Buzzfeed and the Daily Beast disparaging ComicsGate, ranging from passive-aggressive jabs to outright vitriol. Marvel artist Bill Sienkiewicz (of Moon Knight and New Mutants fame) invoked his perceived authority on social media to condemn it as a haven for bullies, further adding that comics had no need for bigots pushing “hateful, misogynistic and plain-old-ugly dogma” allegedly aimed at reviving an old boys’ club. Vulture’s Abraham Riesman on August 29 that year not only railed against a collective of angry reactionaries capitalizing on bigotry, but also painted an image of a united front standing up to such mobs, citing bestselling creators Nicola Scott, Tom Taylor and Gabriel Rodriguez, among others, as being on the right side of history.

That united front also took the form of ideologues (including insiders and editors like Bleeding Cool’s Johnson) openly endorsing de facto blacklists against those who didn’t share the “correct” socio-political views, if not showed apparent hypocrisy over their peers and supporters unprofessionally harassing pro-ComicsGate supporters. This extended to attacks on sympathetic voices like ex-Marvel illustrator Mitch Breitweiser and his wife for guilt by association, despite having no direct involvement. More than just echoing the old CCA, this betrayed a cliquish component in the mainstream’s censorious nature, which ironically seemed lost on such cheerleaders.

A more flagrant escalation could be seen in the case of indie publisher Alterna Comics. On September 3, 2018, CBR’s Renaldo Matadeen used an article about the departure of letterer Micah Myers from the label, over disagreements regarding its social media policy no longer allowing the user of block chains “that would directly affect our stance of full inclusion for readers and creators”, to insinuate that the man in question was fired for not unblocking pro-ComicsGate accounts, lest his unnamed book be cancelled. This opened up accusations of bigotry and malice from pro-industry advocates, including Comic Book Yeti owner Matt Ligeti.

Such grounds for inviting outrage, however, were in spite of Alterna’s stated refusal to be discriminating over both its audience and who it publishes, while founder Peter Simeti further criticized CBR’s reporting as being based on misinformation. While supporters availed of the company’s Etsy storefront, resulting in October of that year being the busiest month it had on record up until then, the subsequent harassment received from the opposition, including “swatting”(false reports made to lure police to unsuspecting innocents), was indicative of how it had become riskier to be associated with the hashtag.

Tensions were also brewing from within, the fallout of which remains a hotly contested subject. Though hindsight suggests the inevitability of loose cliques forming among pro-ComicsGate creators, be it over ideological or financial grounds, some of these grew more vocal in seeking dominance. As recounted by Bounding into Comics’ Donald Green on September 22, 2018, firebrand writer Vox Day attempted to co-opt the hashtag, which commentator Micah Curtis a few days later suspected as being an attempt to push his personal agenda.

While this floundered amidst significant pushback, it put conservative author and fellow contributor Jon Del Arroz on the spotlight due to his connections with Day, despite not sharing his views. By June 24, 2019, he used his position of prominence to launch vocal, if not egotistical crusades against “ComicsGate grifters”, openly decrying the left’s perceived subversion of his movement (which included in his eyes the presence of LGBT characters) and supposed enablers.

From then, things grew more complicated. Around the same time, a group of trolls known only as #WarCampaign, had begun harassing anyone not seen by those using the hashtag as being “pure” or genuine enough, in an ironic echo of the “social justice warriors” they openly scorned. It also sparked considerable infighting on social media and behind closed doors, which was further dragged along by the combative personalities of people like Van Sciver over accusations of hypocrisy, if not complicity.

It didn’t help that all these coincided with a lawsuit filed by Meyer against Big Two comic veteran and activist-writer Mark Waid over the latter’s allegedly "tortious interference with contract and defamation" with the release of Jawbreakers. This led to indie publisher Antarctic Press, originally meant to print the work, all but cutting ties with the author, if later on revealed to be under pressure from Waid himself. This went on until December 2020, when it was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. Though both parties claimed victory, it nonetheless did little to paint either side in a good light, further blemishing the public image of ComicsGate.

These developments weren’t lost on the opposition. Ex-DC artist Matt Battaglia, writing for The Federalist on May 18, 2018, cynically condemned everyone involved for fostering what he saw as a zero-sum game, and for emboldening the very mainstream being critiqued. The New Statesman’s Dorian Lynskey went further in a November 21 op-ed, decrying a reactionary hate-mob against “bastions of liberal thinking”, in which any open association was tantamount to career suicide. Bleeding Cool’s Johnston on June 25 the following year all but reveled in how his claims about the movement imploding before his very eyes (even while reappropriating Del Arroz’s accusations) were being vindicated. To say that critics had a field day would it selling it short.

It’s little wonder, then, why Dynamite ultimately disavowed ComicsGate by August 2020 after significant pressure. Meanwhile, more creators quietly distanced themselves from the movement, if not cut ties. Notably, TenNapel publicly abandoned it altogether, whether due to sharing Del Arroz’s outspoken views vs. “unprincipled leftists” (albeit in the service of religious conservatism), being targeted by #WarCampaign trolls. He also blamed supporters for acquiescing to LGBT audiences and allegedly conspiring with Dungeons and Dragons artist Tess Fowler in invoking harassment and charges of bigotry against him.

This isn’t to say that this was the end of ComicsGate once the worst was through. The name has persisted (complete with its own “official” website) thanks at least partially to the efforts of its original figureheads, even if their more ardent supporters’ discourse became subsumed into the wider culture wars. Both Meyer’s Jawbreakers and Van Sciver’s Cyberfrog, meanwhile, proved profitable enough to see follow-ups well into 2023, with their creators’ respective publishing companies attracting additional talent.

Nonetheless, the damage had been done, its notoriety all but sealed.

The Present and Future

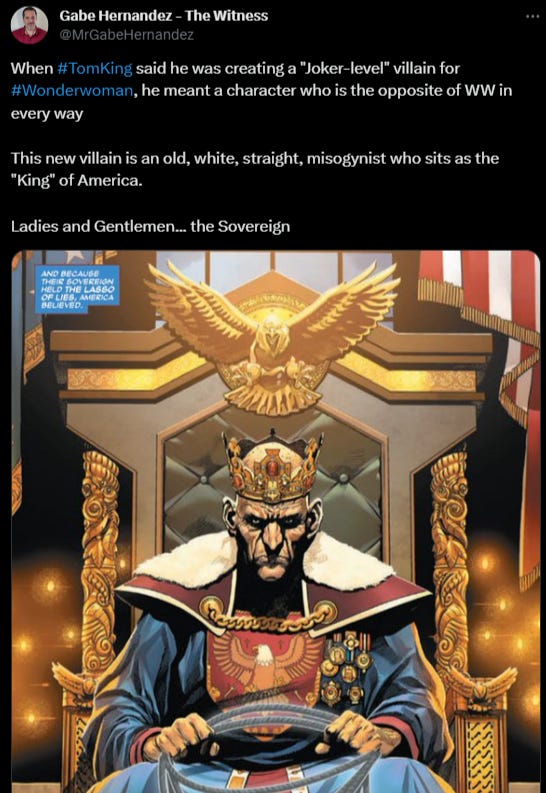

On the surface, it can be tempting to declare ComicsGate an outright failure. The Big Two remain a dominant presence in the Anglophone market as of Q4 2023. Vocal creators like Waid have continued doubling-down on the same politicization and grandstanding as before, if not to a greater degree. Meanwhile, any vocal criticisms towards the industry, as shown by Bleeding Cool’s Johnson in his December 11, 2023 op-ed, are either patronizingly downplayed or treated with contempt.

ComicsGate’s alternative vision where the artist need not fear the censor was also nothing new. Image Comics, founded in 1992 to foster “creator-owned” content, had already proven that indies from superhero fare to more experimental works could not only hold their own against the Big Two, but could even be profitable with enough effort (as seen with The Walking Dead and Invincible). Crowdfunding and direct distribution, meanwhile, had grown over the years, allowing individuals and smaller indie publishers to stand on their own, in spite of the added risks from removing the industry middleman. Why have another initiative when there’s an existing and supposedly “safer” bet?

What made this particular movement stand out, however, wasn’t just its combination of more sophisticated self-publishing, vocal criticism from fans and open dissent from people within the industry itself. Rather, it’s that such ideas had grown enough in visibility and profits to be deemed iconoclastic, in a way that neither Image nor IDW could be. If anything, it came off almost like an outright threat to the prestige enjoyed by the industry’s mainstream for so long.

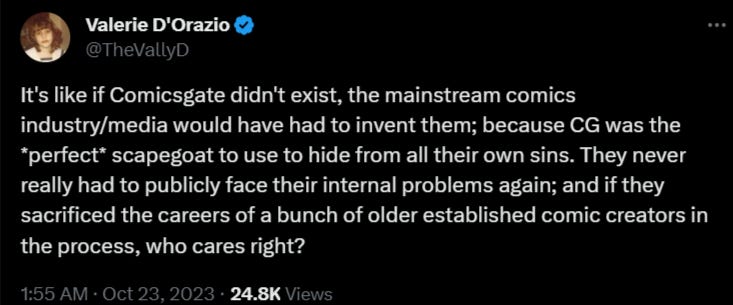

In another echo of GamerGate, the hashtag is simultaneously declared dead and, if former DC editor Valerie D’Orazio is to be believed, brandished as a convenient boogeyman with which to stifle any internal dissent, even if this meant sacrificing the careers of “a bunch of older established comic creators in the process”. More than confirming what critics had long suspected, this has been further reinforced by biased mainstream media coverage (with Wikipedia flagrantly so), making any fair assessment a tall order. Yet despite discontent from Western fans and the continued shift towards manga, it seems as though the mainstream has won. Looks, however, can be deceiving.

After putting up with harassment and external pressure, Alterna Comics permanently broke off from Diamond Comic Distributors, the primary source for Comichron’s reports and a major component in the supply chain that has been relied upon by the industry, on April 2020. Echoing what some Japanese publishers were already doing prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, its decision to distribute directly through its online storefront seemed at a glance like career suicide for an ostracized Western indie publisher. According to Simeti in a September interview, however, it managed to expand its consumer base by 20% and maintain some semblance of normalcy, despite hurdles. This, coincidentally, allowed it and its affiliated creators to perform better than their mainstream competitors even as the latter dodged collapse.

Alterna wouldn’t be the last. In addition to DC moving its wholesale services elsewhere on June 5, 2020, as reported by Comichron founder John Jackson Miller, Image had announced on May 24, 2023 that was it similarly pulling out of Diamond in favor of Lunar for direct market distribution. While not enough to dethrone the existing status quo, with the distributor still supplying 71% of Western comics, this has only reinforced the sentiment that it’s not quite the cudgel it had once been.

According to ICv2 data collected long-running blog Comic Book Revolution on January 11, 2024, while the Big Two still dominate the Top 100 single issue charts as of December 2023, encompassing anywhere from 18,000 to over 65,000 units sold (Marvel at 49% of placements and DC with 37%), there’s a noticeable drop whereas the likes of Image were able to get 11%. This has been attributed to bad editorial oversight, while DC’s seemingly strong annual standing is found to be disproportionately reliant on Batman material. Given how it parallels with what’s seen by The Economist as a marked decline for comic adaptations (and the MCU specifically), with reasons ranging from fan dissatisfaction and mounting expenses to deteriorating quality, this is little coincidence.

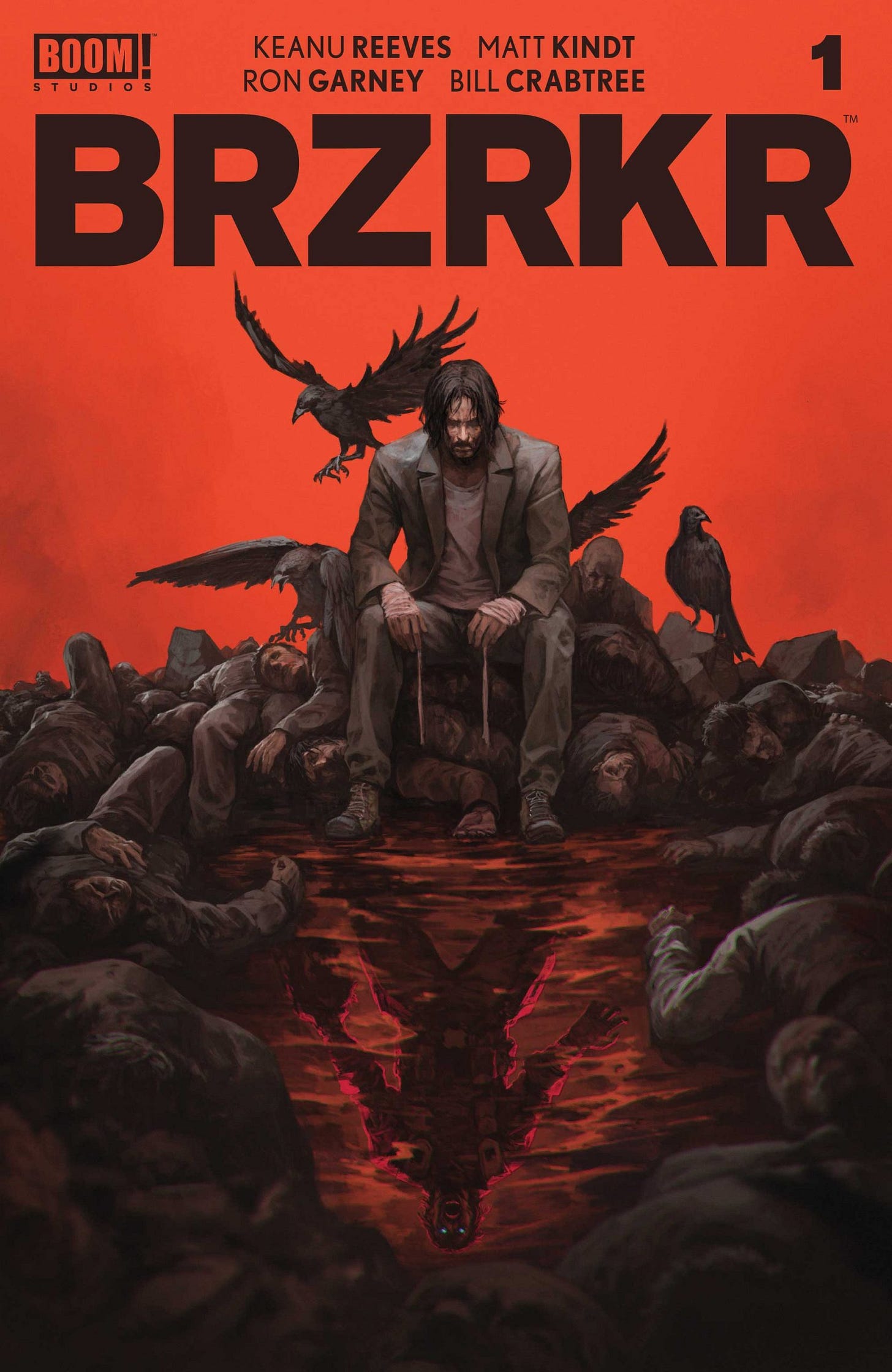

There’s also a broader yet tangible shift away from business-as-usual, whether or not the creators in question would have ever considered themselves sympathetic to ComicsGate at all. Among smaller publishers recognized by the industry, the partly-crowdfunded action-fantasy BRZRKR (co-written by Keanu Reeves, Ron Garney and Matt Kindt) has made waves, with the first issue notably selling over 600,000 copies within a month following its January 2021 launch, the biggest among American comics since Marvel’s Star Wars #1 in 2015. More than just its star power or giving small indie publisher BOOM! Studios a budding multimedia contender, the series’ mix of quality art and fascinating ideas have allowed it to stand out compared to more established franchises.

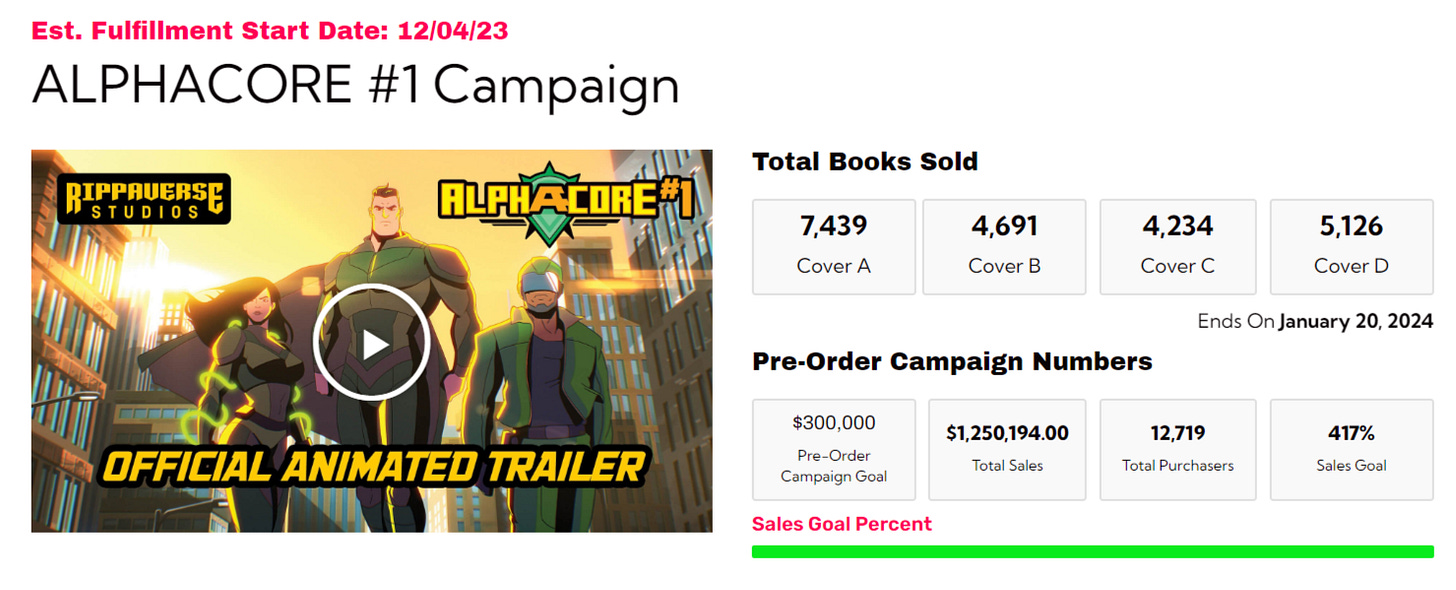

Then, there’s the part of indie scene largely ignored by the mainstream. On July 11, 2022, libertarian commentator Eric July announced the launch of his new independent comic publishing house, Rippaverse. Formed both to “put his money where his mouth is,” as the founder remarked in a Fox News interview a few days later, and as a response to “woke culture”, the expressed goal of avoiding the same mistakes with comics caught fire on social media. Whether it’s the $1.7 million in preorders for July’s maiden series Isom less than a week after launch, or the first issue of Dixon’s Alphacore reaching over $1.2 million by January 2024, it doesn’t seem like a flash in the pan.

This was met with vocal backlash, with the African-American July having faced censorship and scorn in social media sites like Reddit, including allegations of hate speech, bigotry, and polarization, despite his repeated insistence of leaving partisanship at the door. Thus, outside a handful of mainstream publications like the Daily Caller and public endorsement from veteran comic creator Mark Millar, one’s hard-pressed to find much mention anywhere in the industry. Yet in a statement posted on June 22, 2023, science fiction publisher Baen Books explicitly cited the iconoclastic Rippaverse as one of the key reasons behind its decision to publish its own comics line, beginning with adaptations of John Ringo’s New York Times bestselling novel series Black Tide Rising, with Dixon also at the helm.

Similarly, other artists who were formerly aligned with with ComicsGate have managed to establish their own stable niches in the indie scene, if not garner even more success. Northcott’s self-published North Valley Grimoire since became one of Kickstarter’s most popular Canadian books ever, and has received its own comic adaptation. Lim’s manga-inspired Kamen America, which evolved from being a parody of Marvel heroines into a legitimate series of its own, has gained enough traction to gain a Japanese fanbase. Meanwhile, RAGS Zombie’s warm reception allowed its creative team to go professional as New Age Ninja Corps and expand on their original concepts. Whether or not they discreetly consider themselves as carrying on the hashtag in their own way, it further drives home how the precedent set is a lot harder to repress than what’s commonly believed.

Granted, flare-ups of drama among supporters in this space still pop up on social media, whether it involves the original ComicsGate cheerleaders, or July’s Rippaverse. Thanks in part to the infighting, the alternative scene that’s emerged since 2017-18 also lacks any catchall name that’s universally agreed upon, though Simeti’s “Iron Age” quip back in August 31, 2021 seems to have caught traction: an “attitude shift” leveling the playing field through independent will and grit. I couldn’t help but agree.

Beyond advancements in self-publishing, parallel platforms, and repeating what Image did for earlier indies, there’s a tangible sense that even as a work-in-progress, the foundations laid years ago are bearing fruit. Regardless of content, writers and artists are increasingly able to maintain the kind of creative freedom that most mainstream ones could only dream of. That fans in return get a greater emphasis on story, characters, and spectacle over politicized grandstanding, have given such works at the very least the potential to transcend the culture wars altogether.

There’s even been a begrudging recognition from a few detractors like novelist Nicholas Ahlhelm as early as July 20, 2020 that the trend of people like the seemingly ostracized Breitweisers “rising above it all” by going off to pursue their own path through their Alliegiant Arts company could be a good thing. Not just for fans, but the wider Anglophone industry at large.

Alas, given the establishment’s simultaneous silencing, chiding and demonizing of anyone stepping out of line, such views still seem more the exception rather than the rule. For better or worse, however, ComicsGate’s legacy is very much here to stay. And if the industry’s mainstream still refuses to heed that, then it need not be surprised if in the future, a new status quo takes its place.

No wonder the establishment still refuses to listen and double down on their changes.